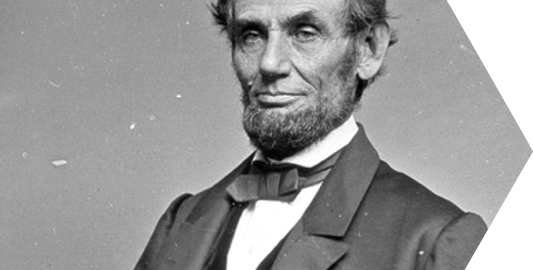

Doctor Defended in Lincoln’s Death

The New York Times

January 3, 1992

Dr. Richard Mudd has worked so long trying to clear his grandfather of complicity in Abraham Lincoln’s assassination that he was dumbfounded when he learned that he would finally get the chance.

“After 75 years, I’m getting tired of the thing,” Dr. Mudd, who is 90 years old, said recently from his home in Saginaw, Mich. “But I’m not tired to the point I wanted to give it up.”

On Dec. 16, an Army panel said it would consider in January whether to expunge Dr. Samuel Mudd’s conviction in 1865 on charges of aiding Lincoln’s assassin, John Wilkes Booth, by setting his broken leg.

The hearing could mean victory for the grandson, who has struggled for decades to win exoneration of his grandfather. The grandson and his family are to go before a panel of the Army Board of Correction of Military Records on Jan. 22 in Washington. Given Life Sentence

Dr. Samuel Mudd, was arrested on April 24, 1865, 10 days after Lincoln was shot at Ford’s Theater. He said he had known nothing of the killing when Booth arrived on horseback at his home in Waldorf, Md., 30 miles outside Washington.

Booth was killed by soldiers on April 26. Dr. Mudd and seven other defendants were convicted by a military commission, with four being sentenced to death and hanged. Dr. Mudd received a life sentence.

He spent four years imprisoned at Fort Jefferson in the Gulf of Mexico and won recognition for helping battle a yellow fever outbreak there. In March 1869, President Andrew Johnson gave him a pardon. Dr. Mudd himself had caught yellow fever, which contributed to his death at age 49.

His grandson has lobbied presidents, Congress and the military courts since the 1930’s, and has won some victories.

President Dwight D. Eisenhower dedicated a monument to Dr. Mudd in Key West, Fla. Numerous state legislatures passed resolutions proclaiming the doctor’s innocence. Presidents Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan wrote the grandson that they were persuaded that the conviction was wrong but said that they were unable to set it aside.

It was not until July, when the corrections board decided it had the jurisdiction to hear an appeal, that Richard Mudd had a hope of getting the official record changed.

The board ordinarily reviews complaints of living service members who claim to have been unfairly disciplined, and it can reopen historic cases.

The board recently restored military honors to William F. (Buffalo Bill) Cody, the 19th century soldier and showman, after his survivors argued that his medals had been unfairly taken away.

Since August, board members have been familiarizing themselves with the case by reviewing material from archives, said Maj. Rick Thomas, an Army spokesman.

After the hearing, the board will deliberate and make a recommendation to Army Secretary Michael Stone or his designate, who will rule on the case. There is no time limit for a decision, Major Thomas said.

* Copyright 2007 The New York Times Company