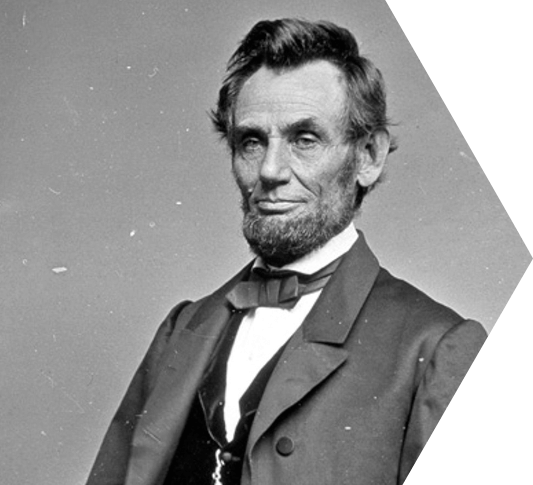

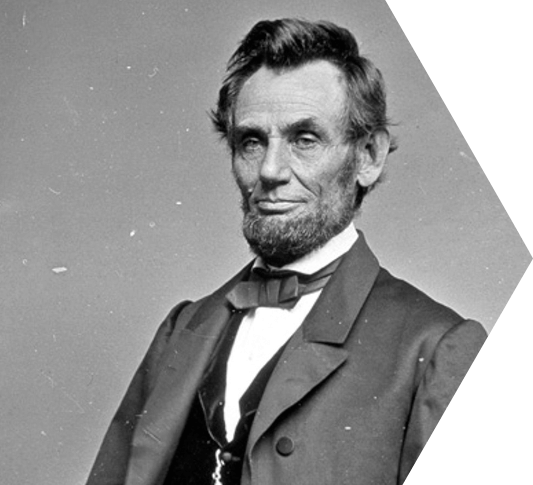

Doctor Who Aided Lincoln’s Killer Is ‘Cleared’

The New York Times

February 14, 1993

More than a century after his death, Dr. Samuel A. Mudd’s appeal to clear his name as a conspirator in Abraham Lincoln’s assassination was finally heard. He won, but it was only in a mock trial.

A moot court here ruled Friday that the military commission that convicted Mudd in 1865 and sentenced him to life in prison had no right to try him in the first place.

Mudd was convicted as a conspirator after he set John Wilkes Booth’s broken leg when Booth arrived at his Maryland home after shooting Lincoln. The doctor later contended that he had no idea the President had been shot.

Mudd’s mock trial was staged on the 184th anniversary of Lincoln’s birth. His case was argued by F. Lee Bailey before a three-judge panel at the T. C. Williams School of Law at the University of Richmond.

“Mudd’s prosecution was one sledgehammer after another upon the Constitution,” Mr. Bailey told the court. Battle for Rehabilitation

No real court has agreed to rehear Mudd’s appeal, but his descendants have waged a long battle to clear his name.

“My grandfather never got a fair trial, so this is a great day,” said Mudd’s granddaughter, Emily Mudd Rogerson, 86, of Richmond.

Two of the moot-court judges, Robinson O. Everett, a retired senior judge of the United States Court of Military Appeals, and W. Thompson Cox 3d, who sits on a military appeals court, ruled that Mudd, a civilian, should have been tried by a civilian jury, not the military commission.

While the moot court did not formally rule on Mudd’s guilt or innocence, the third judge, Edward D. Re, said the case was insufficient for a conviction.

“I cannot resist the temptation of saying I have very serious doubts whether an impartial military panel distanced from the moment would have found the evidence presented was sufficient beyond a reasonable doubt,” said Judge Re, a retired senior judge of the United States Court of International Trade.

The moot court’s ruling is not binding, but Mr. Bailey said he hoped that the Army would use it in considering whether to erase Mudd’s conviction.

“The jurisdiction issue was key,” Mr. Bailey said. “And when three distinguished judges agree the conviction was wrong, I am obviously pleased.” Question of Jurisdiction

John Paul Jones, a Richmond law professor, said he organized the mock trial using the assumption that Mudd appealed his conviction to a military appeals court, a body that did not exist in Mudd’s time. Mudd died in 1883.

Booth shot Lincoln on April 14, 1865, five days after the Civil War ended. Twelve days later he was gunned down by Union soldiers in rural Virginia. ‘Monumental Embarrassment’

The prosecutor in the mock trial, John Jay Douglass, argued that the war was not really over when Lincoln was shot because sporadic hostilities continued for months. As a result, the military court that convened in June was within its rights to try Mudd and seven other accused conspirators, said Mr. Douglass, dean of the National College of District Attorneys in Houston and a former commandant of the Army Judge Advocate Generals School.

Mr. Bailey argued that the military commission that convicted Mudd and the seven others “was set up to satisfy the monumental embarrassment of lax security that allowed the President of the United States to be assassinated by an amateur.”

Mudd served four years of his life sentence before being pardoned by President Andrew Johnson. The conviction stood.

Mudd’s descendants have argued that Mudd did not realize until too late who his injured visitor was and that the doctor should not have been tried by the Army.

The Army Board for Correction of Military Records has agreed that the military lacked jurisdiction. But last July, William D. Clark, Acting Assistant Secretary of the Army, rejected setting aside the conviction, saying it was not the role of the board to settle historical disputes.

* Copyright 2007 The New York Times Company